The Bloomingdale Historic District is a group of 1,692 contributing resources bounded by Channing Street to the north; North Capital Street to the east; Florida Avenue to the south; and 2nd Street to the west.

Bloomingdale is significant for its status as one of DC’s largest cohesive row house neighborhoods. Its development began with the arrival of a streetcar line and was continued rapidly by a small group of speculative developers and builders. It boasts a large stock of row houses of high-quality design and materials, houses intended to attract stable middle-class residents. The size and quality of the architecture illustrate that the success of speculative development for DC’s rising middle class was all but assured during the years in which theneighborhood was built.

Bloomingdale also demonstrates the architectural transition of DC’s row houses away from fanciful three-story Victorian buildings of the early 1890s to the more regular, two-story, front-porch row houses of the 1910s. Bloomingdale is also one of the first large developments in DC laid out in conformance with the Permanent Highway Plan of 1893, which standardized the layout of new subdivisions beyond the city’s original boundaries.

These factors, along with Bloomingdale’s prominent role in the struggle to abolish racially restrictive housing covenants in the District and nation from 1907-1948, make the neighborhood significant. The Bloomingdale Historic District’s period of significance is 1892-1948.

Bloomingdale and the Fight Against Racially Restrictive Housing Covenants

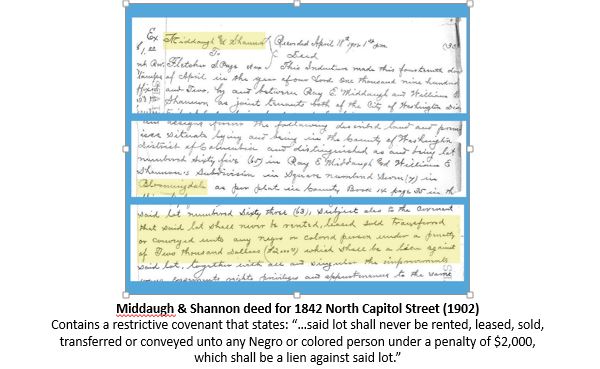

Bloomingdale is associated with events related to racially restrictive covenants, specifically, the large number of legal challenges to the racially restrictive covenants that were the primary means by which developers and residents attempted to keep the neighborhood segregated. Bloomingdale is associated with the two DC cases that advanced to the Supreme Court and were part of the landmark 1948 decision that ruled racially restrictive covenants unenforceable.

Bloomingdale played a major role in the civil rights history of DC and the United States. A number of Bloomingdale’s developers used racially restrictive covenants. These prohibited sale or rental to African Americans in deeds for lots and houses. Bloomingdale was blanketed with racial covenants, but from the start of development was home to African American residents.

By 1907, white residents organized to enforce racial covenants in deeds. By 1913, the local citizens association passed a resolution opposing real estate sales to African Americans. Bloomingdale’s racial covenants by agreement, combined with those placed by developers, restricted nearly all housing between First and North Capitol streets from R Street to Channing Street. Of the 43 legal challenges to racially restrictive covenants in DC documented to date, almost half were associated with Bloomingdale.

Washington County Transforms from Rural Zone to Urban Residential Neighborhoods

Bloomingdale is associated with the transformation of Washington County from a rural to residential area. Until the late 1880s it was a rural zone of farms and estates owned almost entirely by three families. With the arrival of an electric streetcar line around 1887, the families subdivided their land. Between 1890 and 1912, Bloomingdale, named for one of the original family estates, developed completely with brick row houses and a few apartment and commercial buildings. It is the first neighborhood in this area to be designed in alignment with the L’Enfant Plan. It had 71 buildings in 1895. By 1912 it had 1,572 buildings.

Bloomingdale differed significantly from its neighbors. Its urban character is typical of row house neighborhoods within the city, but its residential character is more similar to suburbs outside of the city’s core, where commercial uses were discouraged. Commercial development is mostly limited to blocks along the neighborhood’s major transit corridors and resembles the neighborhood’s housing stock in style and scale. Long, cohesive rows illustrate developers’ confidence in a good investment return. This wholesale building process eliminated opportunities for later in-fill development. As a result, most of the original housing is intact.

Bloomingdale’s evolution represents work by many of DC’s well-known developers and architects, including Harry Wardman, Middaugh & Shannon, Francis Blundon, Thomas Haislip, Joseph Bohn, Albert Beers, William Allard, Nicholas Grimm, and George Santmyers.

Bloomingdale’s Famous Residents

Bloomingdale was home to a number of famous leaders, including several who worked to break down racial barriers in the neighborhood. In 1941, NAACP attorney Charles Hamilton Houston partnered with real estate broker and lawyer Raphael Urciolo in an attempt to void racial covenants on Adams Street and to sell houses to African Americans. After the courts upheld the covenants, Houston and Urciolo shifted their focus to Bryant Street, where two important legal cases arose. In suits brought against an African American couple, the Hurds, and Urciolo by Frederic and Lena Hodge of 136 Bryant Street, the District Court upheld the covenants on all four properties.

When a consolidated appeal of Hurd v. Hodge and Urciolo v. Hodge was struck down, appellate court Judge Henry White Edgerton dissented, calling racial covenants unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed Edgerton’s dissent. Following testimony by Houston and NAACP attorneys, the Supreme Court held that enforcing racial covenants violated the 14th amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Bloomingdale was also home to American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers in 1902-1917 and Senator Edward Brooke, the first African American elected to Congress in the 20th century.

Bloomingdale’s Architecture

Bloomingdale is notable for its distinguishing architectural styles and aesthetic values that contribute significantly to the heritage of DC. Its row houses are remarkably intact, substantial in size and materials, and offer quality design and craftsmanship. Built largely between 1892 and 1916, the row houses are generally the product of teams of developers, builders and architects, executed in late Victorian/Edwardian and early-20th century styles. The rhythm of repeating and alternating projecting bays, turrets, and rooftop ornaments of the late 19th-century examples, and the front porches and dormer windows of the early 20th-century ones, give Bloomingdale its human scale and rich visual quality.

The collection of row houses offers a visual lesson in the transition of the row house form in the city from the Victorian era to the 20th century. Beginning in the early 1900s, the Victorian and Edwardian row houses, replete with ornament, give way to more modest, subdued, regularized row house forms, characterized by full-width front porches and low-lying roofs. Subtle stylistic shifts in these periods become apparent, including changes in bay configurations, ornamentation preferences, and roof treatment.

Historic Designation

DC Preservation League nominated the historic district on behalf of the Bloomingdale Historic Designation Coalition (BHDC). The BHDC is a group of Bloomingdale residents who raised funds to hire local history consultancy Prologue DC to write the historic district nomination and those who supported designation.

The DC Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB) designated the historic district in July 2018 for meeting criteria for events, history, architecture & urbanism, artistry, and work of a master. Click here to read the HPRB decision.